The Story of Joseph ENGLING Extracts from the book by Rene Lejeune

Table of Contents

The Disarray

Joseph arrived on 31st July at Bois-Bernard. There he stays until August 7th. He learns that his friend Clemens Meier is seriously injured, the point when he wondered about his vocation. On 8th August, Joseph’s Battalion returned to the front line, west of Douai, between Bois-Bernard and Fresnoy. He is once again in an observation post, under the orders of his friend Edmond Kampe. Through his glasses, he tries to find out what is happening on the British side.

An intense activity is taking place. One must conclude that an offensive is being prepared. The initiative is now spent on the other side. The German units, decimated by the deadly fighting in the Spring and Summer, have not been replenished. The Regiments are reduced to that of a quarter of their normal size. Opposite, the enemy brings fresh troops. Four Canadian divisions come to take a stand. For the whole Western War Front, there are in all 3 million German soldiers as opposed to 6 million allied soldiers. We learn that in Germany itself, the confusion begins to take the form of protest, a silent revolt. All this affects the morale of soldiers at the Front. An atmosphere of crisis pervades in their minds. The huge war machine is running more by the effect of momentum. On 17 August, Joseph was appointed commander of an observation unit. With a subordinate, he goes to his new position, the right wing of the local front. The soldier who was accompanying him is in a bad mood against the plague of “monkeys” of the General Staff in their hideouts at the rear. He holds subversive intentions. He has been a soldier for six years. The position is clear. If those people up there do not put an end to all this ‘s..t’, he will take it upon himself to end it. It alludes to desertion. Joseph is listening to his comrade. He keeps calm. He does not approve of it. His sense of duty is too great for similar ideas to touch him. This is not the first time he has heard such remarks. In the troop, due to the failure of successive offensives, thoughts of betrayal occur but most often due to fatigue and a desire to end it all. In this month of August 1918, nobody feels like a military victory any more. The German Army is fighting in the crater of a volcano. Joseph has in his mind painful thoughts which are strange for this boy of Prussia. “I do not hide from my duty. I shall fight and endure the overwhelming tasks. I’m not quite convinced of the truth of an ideal design of the Fatherland; nevertheless I do not escape from my duty…… In truth, I am not convinced that the ideal of the Fatherland rule will take place and in my mind everything is confusing …”

At that time Joseph carries the responsibility of the observation posts in his sector. Edmond Kampe was recalled to Germany to become an officer. Joseph replaced him at the front. This point shows how much the reserves were shrunk in the lower echelons. “I now have three men under my command. I realize what it means to be a very good leader. It is already difficult to satisfy this small number, let alone an entire company!” For one month, intense activity on the British side leads one to think that the next offensive outbreak will be launched in the area of Vimy. The network of trenches have become a familiar universe of the combatants: “Our sector looks like villages with their streets. Each gallery is a village or city. The trench itself is the street, shelters are homes. The galleries being the connecting link between the trenches are the roads. In a sector like ours, one gets lost more easily than in a green field, although there are signs”.

What he sees from his observation post, makes him suspect that the British attack is imminent. Two or three days at the most. Joseph was not mistaken.

On the way to Cambrai

On 1st October, at nightfall, the 25th Reserve Infantry Regiment received an order to pack up and move to the rear. The withdrawal did not say anything about the brave troops involved. Having not been engaged in battle for weeks, they are regarded as fresh units. They will surely move them to an area under fire. They do not fail. For two weeks, the battle rages over most of the Western Front. Near Ypres, the allies have achieved a breakthrough. Along the Lys, where Joseph was previously stationed, they have regained an area that the 15th Division of the German Reserves had held two months earlier with heavy losses. St. Quentin falls to British hands. The situation was critical. The German high command had to move its reserves. Also, the British broke the German line North of Cambrai. “That is where the 25th Reserve Infantry Regiment should be thrown to plug the gap”. Then the Regiment was entrained at Pont-de-la-Deule station and headed south-east. Everything was done in haste. The danger which they will face must be extreme.

The Regiment arrived to the North of Cambrai. The Canadians advance towards Sailly-Eswars, surrounding Cambrai to the north. This danger leads to the German command to counter-attack. In late September, a Wurtemburg Division is launched in the battle, and pushes the allies until the Douai-Cambrai railway line. At the cost of heavy losses this division was decimated and needed to be reinforced by the 15th Reserve Division.

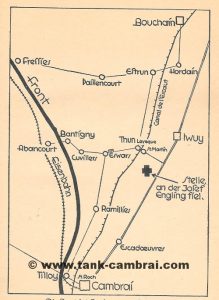

Joseph was in the train with the 25th Infantry Regiment and stops at Bouchain, a dozen kilometres North of Cambrai. He takes up its quarters. The city is in a sorry state. Almost every night, it was bombed. In the middle of their second night at Bouchain, departure is announced. The Regiment advance, heavily loaded in darkness, on the road to Cambrai. At Thun-l’Eveque, it moved west to Eswars and takes up a position between the village and Bantigny. The troop is hungry and exhausted. Morale is at its lowest under the incessant artillery and aerial bombardment.

The 4th Company – that of Joseph – is sent to a position North-West of Eswars, near the village. They arrive at 6am. Joseph Engling had reached the day and place of his death, Friday, October 4, 1918.

In the morning light, he faithfully pulls out his diary: “At Eswars near Cambrai. The relief was unusually fast this time. On the evening of October 1st, the advanced troops of a new Stormtrooper Regiment arrive suddenly. The next night we leave our position and advance for 4 hours. We are now ready for action, while the ‘Tommy’ constantly sends its shells closer and closer. At 50 metres from me, there is a military cemetery in an old field where several already dug graves seem to wait for us. But we are still not there! Today I am fasting involuntarily. The company responsible for our regular supplies has received just two rations for us. Because of our movement, it has not yet been able to correct this mistake. That’s why today none of us has had anything to eat. The field kitchen will only come tonight.”

The writing is exceptionally uneven. Joseph wrote these words in an uncomfortable and totally precarious situation. With these words the diary of Joseph Engling concludes. It has run since the age of 12 years. Over the years, it has become a moving witness to a prodigious spiritual uplift. Joseph is twenty years old. He has only a few more hours to live.

Struck in the heart

During the afternoon, Joseph visits Paul Reinhold, a member of his religious group from Schönstatt. They have a long exchange. Paul found his friend pensive, melancholy and it seemed a veil covered his eyes and words. When they part, it will be forever. Joseph Mehl, another of his friends at Eswars, also spent a few moments with Joseph. He shows him where the cemetery has graves dug: “I prepared my grave there,” he said. Joseph Mehl replied: “You’re crazy, I do not believe anything.” So Joseph Engling talks about a shocking premonition: “This night, Mother of God will accept my sacrifice.” Then he was called. He returned and said: “I must join the advance guard of the Stormtrooper Regiment”.

Paul Reinhold will be taken prisoner by the British near Le Cateau. He will disappear into captivity without leaving any trace. The last person to have seen him is Joseph Mehl. The prisoner was in the back of an British truck, his arm in sling.

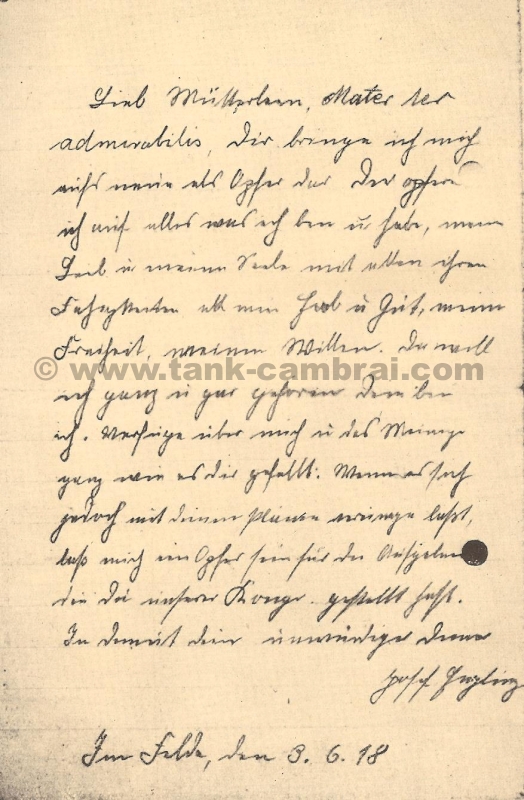

“He knew that the next day I would be on leave. He took a sheet of paper, wrote a few words and gave it to me saying: When I fall, send of my death to this address. Then he gave me his hand, looked me straight in the eye and said: I wish you a safe way home. Make my wishes become true. Our little Mother is in my home waiting….. I’m ready. Everything is in order!” A final smile, and the two friends parted.

Hunger grips Joseph. On the other side of the street there is a field where potatoes have just been harvested. He picks up a bowl full of tiny potatoes. He makes a fire in the hangar at the nearby farm and cooks his small harvest. The water had barely begun to boil when he was called. His comrade Nicolas Gilgenbach tells him that they must leave immediately to join the advanced guard of the Stormtroopers. Joseph prepared hastily. The potatoes are not yet cooked. Whatever, he removes the bowl from the fire with the half raw potatoes. He starts with the small group. “Once again, I could eat my hunger, maybe this is the last time,” he said while walking with Nicolas. He continued, with a strange feeling: “If I should not return, I say unto you, goodbye. If it is not in this world it will be in the afterlife. If by chance you meet Edmond Kampe, convey him a last greeting on my part”.

Nicolas takes a look at his comrade. This tone is not at all usual for him. “We are so often mounted on the front line and nothing has happened,” he said. Joseph with an outline of a smile: “It was always a slight hunch but now I have a definite feeling. Finally, if God wants it, it will happen.” Joseph shakes hands with his friend, and hastily follows in the wake of the small troop, which has eight men in all.

At dusk, the artillery are firing on the locality and also on the countryside around. Joseph and his comrades reach Thun-Saint-Martin. From there they must turn towards Cambrai. The intersection, not far from them, where the Thun road joins the main road from Cambrai, is particularly targeted by artillery fire. The small troop would like to avoid this trap. At about 200 meters from the crossroads, they enter the field and lie down against an embankment until the firing has calmed. A pause intervened and the soldiers resumed their march through the fields separating into two groups.

Then comes the fatal moment. A whistling of shells. The salvo is directed on the crossroads. A shell fell close by. It seems that they are targeted and the shell is meant for Joseph Some shrapnel hit his front and heart. He was killed on the spot. Joseph Engling was the only victim of the small troop. Heaven comes to accept his sacrifice freely consented. The next morning only when they are back at Eswars, after having wandered all night through the fields, may Joseph’s companions notify of his death. The informer, Nicolas Gilgenbach muttering: “Oh this kind Engling! He was a faithful comrade and feared God”. The same day, the body is buried. Probably in one of the shell holes that dot the field of death. The confused situation in this sector of the front, does not allow transport to the cemetery, not far away. As always, the personal belongings found on the body were sent to his parents …

His example

On 21st October 1918 the black edged communication, dreaded by families, arrives. It is dated October 10th. Trembling, the father opens. The paper bearing the letterhead of the 4th Company of the 25th Regiment of the 15th Reserve Infantry Division: “The Company carries the sad duty to share with you the news that your son, Joseph Engling musketeer, fell on the field of honour, October 4th 1918, at dusk. The Company mourns the loss of this brave comrade; it will always keep him in its memory. Signed: Kurt, Second Lieutenant Reserves and Head of the Company.

On October 7th Paul Reinhold wrote to Father Kentenich: … “The death struck suddenly without a priest being present. But I am convinced that he has left this life in a state of grace. The Mother of God who he beloved and for whom he worked on the front, called him close to her. Since our group chose the theme of apostolate, Joseph was particularly active in the field, through speech and writing, but it is mostly by his shining example that he was trying to do good. He always helped the chaplain of the Division, he announced religious services in the Company, decorated the altar, served Mass, etc. His availability and kindness brought him the admiration of his comrades. They were completely devastated when they learned of his death”.

Concerning the 25th Infantry Regiment

The archives indicate that the 25th Infantry Regiment was split into two and became the 15th and 208th Infantry Division. Reading the book by Rene Lejeune, it is clear that Joseph Engling served on the Eastern Front with the 15th Infantry Division. Meanwhile, particularly on 30th November 1917, during the Battle of Cambrai, the Regiment had lost many men. It therefore appears that Joseph Engling was sent to the 208th Infantry Division at the Western Front. His Regiment was on the front at Cambrai between 19th September to 8th October 1918 and then from 24th October to 4th November in Valenciennes, having retreated under pressure from the Canadians.

The circumstances of his death and his burial

The Canadians were positioned on the other side of the canal. Joseph Engling was probably killed by artillery fire aimed at the National Road from Cambrai to Iwuy to disorganise the retreating Germans. Joseph Engling having been killed on October 4th, it is likely that his comrades, they could not do it the same day, were able to recover his body the next day. He was the only one killed and it is not in the ‘No Man’s Land’. (see also p. 104, book by Rene Lejeune where Engling tells how he will recover the body of a friend). Joseph Engling also cites the proximity of a small military cemetery and pre-dug graves. Despite the confusion, it is probably not likely that he was just buried in a shell hole but maybe in a provisional cemetery in the area of Thun St.Martin and the main road. We currently do not have the actual cards or proof indicating the position of British or German provisional cemeteries at the time in that particular position.

Confusion

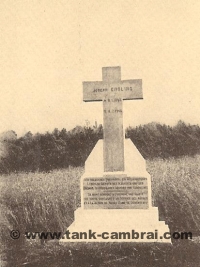

It is therefore reasonable to assume that Joseph Engling has been temporarily buried in a small cemetery of Thun Leveque – Thun Saint-Martin, which has since disappeared. His name has been summarily focused on the tomb because it is true that on October 5th, the situation was becoming increasingly worrying and that soldiers had other defensive priorities, burials had be carried out very hastily. The tomb had to be marked only with a helmet on a cross or often a piece of wood, even the helmet often fell to the ground with the name written on it. Also an artillery bombardment during the final offensive on October 9th could have caused the loss of the exact location. Finally, burials in formal cemeteries was not carried out until after the war as late as 1924.

The organization of cemeteries

It is also important to know that fifteen days after the armistice was signed, the Germans had no right to stay in France. The French were in charge of organizing the German cemeteries and to implement the consolidation of the bodies. The work lasted from 1919 to 1924. The British also worked for the burial of the bodies and created their cemetery on the road to Solesmes dedicated to the soldiers of the liberation of Cambrai. Thus the bodies of soldiers buried in the surrounding villages or recovered during the work of clearing, were then brought back to the Solesmes Road. It is therefore more than confident that the German bodies possibly buried in this small provisional cemetery beside the road were finally exhumed and returned to Cambrai.

The Ossuary Cemetery Solesmes Road

Whenever a doubt remained about the formal identity of the soldier, officials were forced to place them in the ossuary and not in individual graves. Only identities of 439 soldiers buried in the ossuary are known (16%), which is low compared to the 2,746 bodies. Joseph Engling had to correspond to this scenario. There was evidence of the presence of his body at this point, without any certainty, whether the remains were his. As a result, there could be no question of individual burial. Thus, it was placed in the ossuary with his companions in misfortune and his name engraved on the plate.

The wrong date of death

One might think that at the Thun-St-Martin/Eswars cemetery, the name was still somewhere readable but the date of death, if it had been stated, had disappeared which has led to another confusion in the future. The date of 1 December 1918 transferred to the ossuary, which in the confusion, can not fall as a simple administrative error. It could also be recovered in the context of the time. The French found themselves with an enormous burden of work and had to manage the burial of their enemies against whom they still had many grievances.

At noted on the web site of the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge it indicates the death of Joseph Engling as October 4th.

Soldiers "unknown" in individual graves and soldiers "unknown" ossuary

It may explain the fact that some soldiers “unknown” are buried in individual graves by the fact that they were buried by the Germans between 1917 (opening date of the cemetery) and October 1918, as foreseen in the guidelines imposed . It ordered a tomb for each individual soldier. Precisely because of this directive, that the cemetery on the Solesmes, the Porte de Paris Road was established and was quickly revealed as too small. The solution of mass graves was also found to be non-satisfactory given the need for due respects to the dead. The ossuary of the road east of Solesmes is therefore post-conflict. For proof, it is not on the plan for 1917.

Municipal Archives

Finally, later municipal archives, are in possession of cemetery lists at the time, containing the names, first names, date of death, Regiment and No. of buried soldiers are identified. Listings where obviously the name of Joseph Engling does not appear.